By: Lori Ann LaRocco, Senior Editor of guests for CNBC Business News

Nick Vyas, Executive Director, USC Marshall Center for GSCM/Academic Director MS GSCM

For a visual reference of world trade, think of it as a plumbing system that carries the flow of goods and commodities through its vast, complex network of pipes and fixtures. Trade agreements are its pipe adaptors, which help expand trade. High tariffs, on the other hand, can check its flow in two major ways: act either as a stopper blocking the flow of trade into a specific country, or as an elbow pipe, diverting the flow away from one country to another. Viewed like this, the COVID-19 pandemic is an extreme weather event, which has brought the entire global trade supply chain and its logistics to a gasping sputter.

While extreme events such as the pandemic are inevitable, an efficient supply-chain network can minimize the damage. Clearly, that has not been the case. And that is because of an imbalanced network distribution.

We have known for years that China dominated the world in manufacturing. However, the reality of this domination was brought to the fore when consumers around the world were not able to find face masks, hand sanitizers or couldn’t even “spare a square of toilet paper”, as Seinfeld’s Elaine would put it.

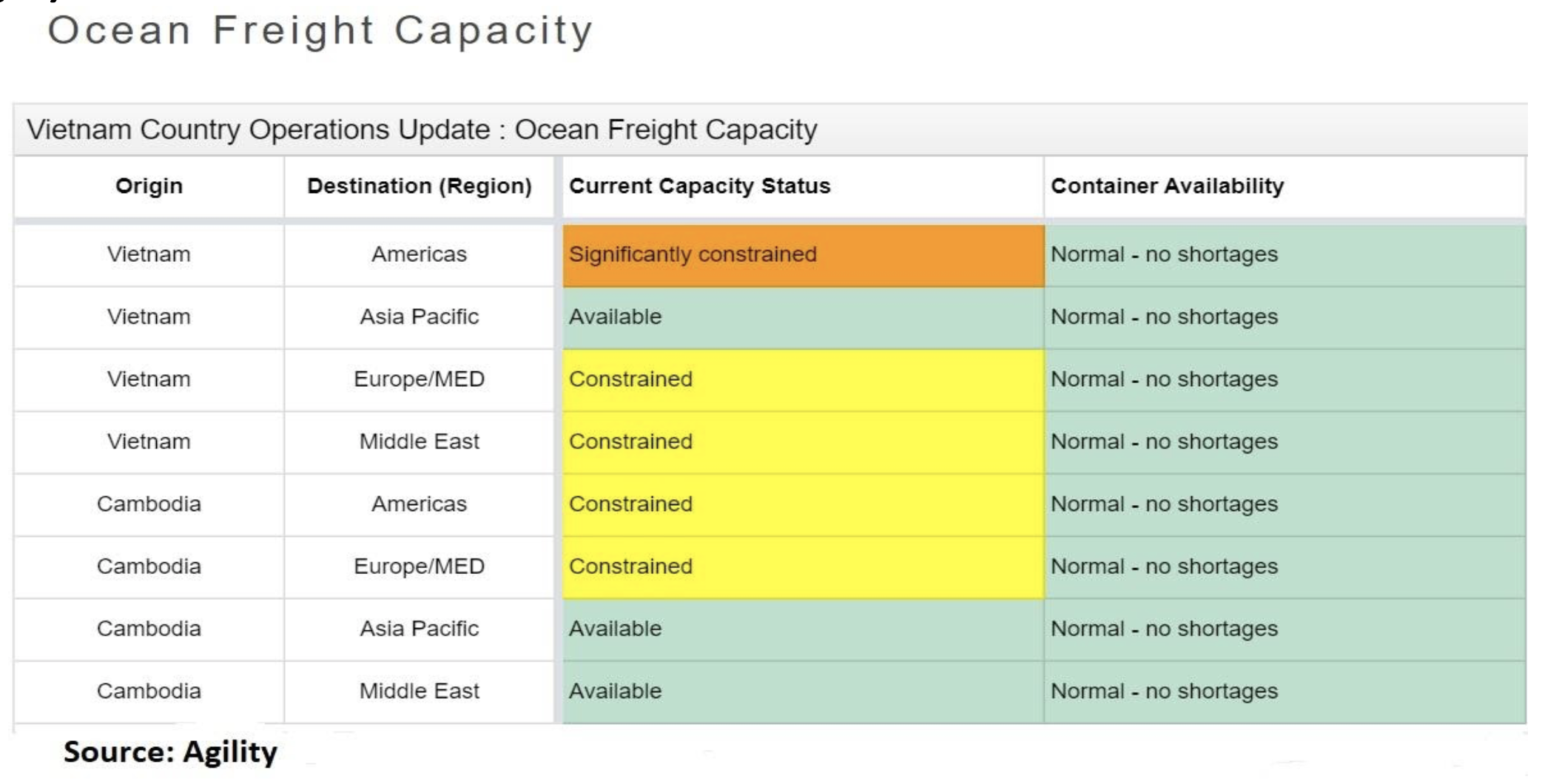

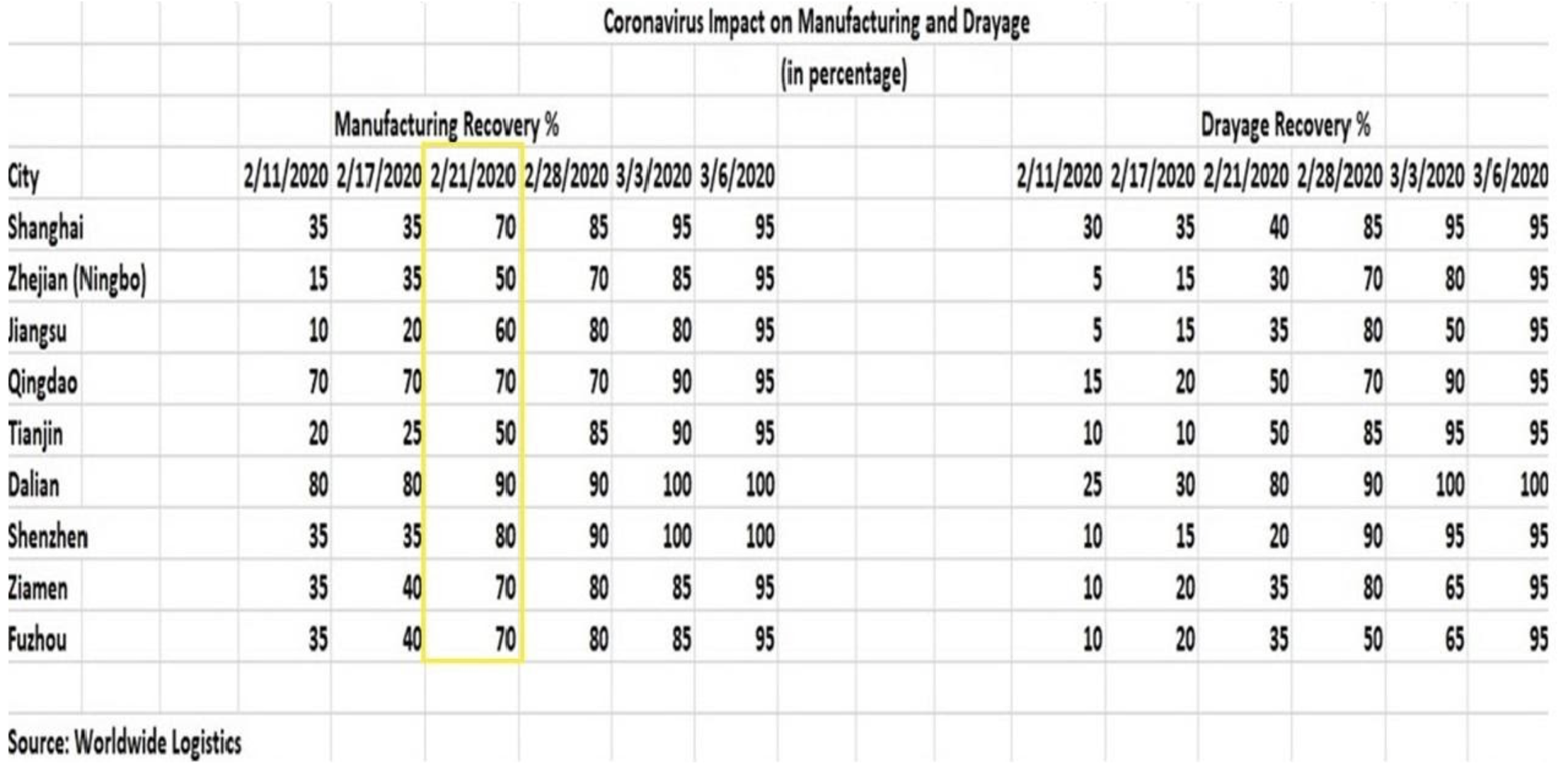

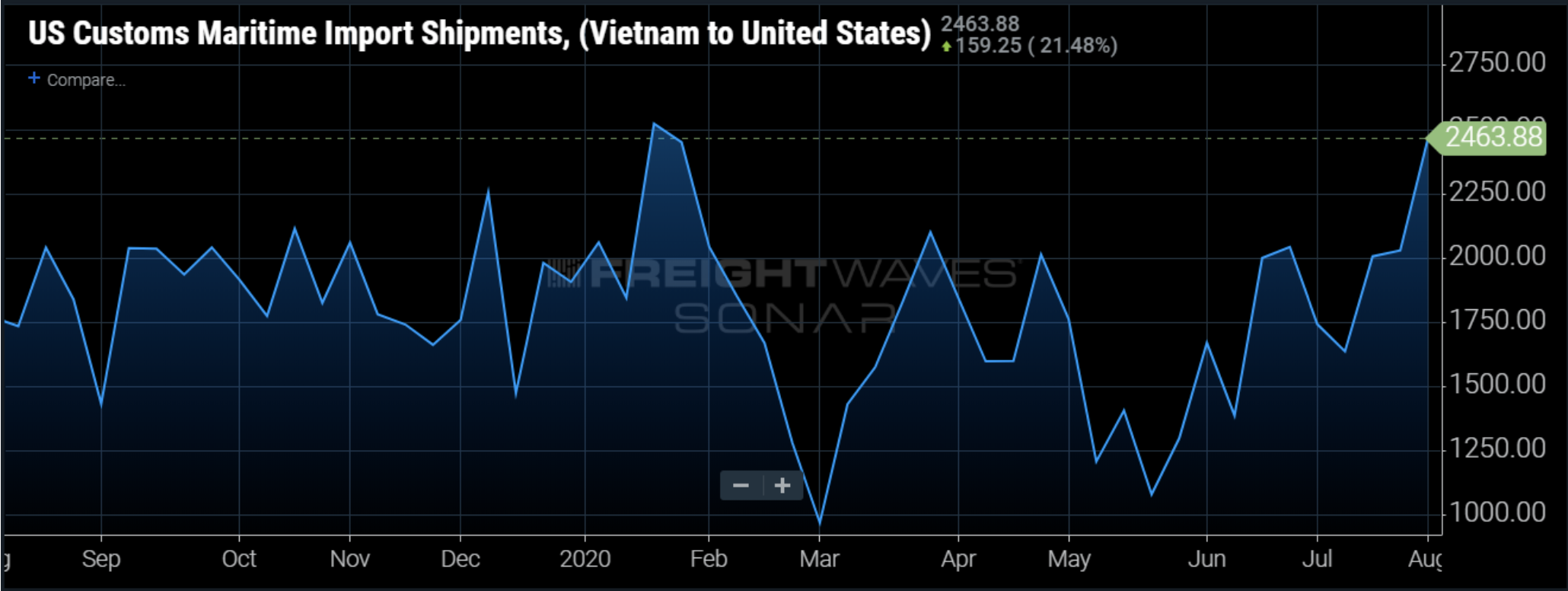

The paralyzing impact of COVID-19 on China-linked trade could be easily chronicled through a timeline of Chinese manufacturing and drayage (the movement of the container by truck or rail) during the Feb-March 2020 period. Since then the cries of moving production out of China have increased globally. (see Fig. a)

Trade War: The Canary in the Mine

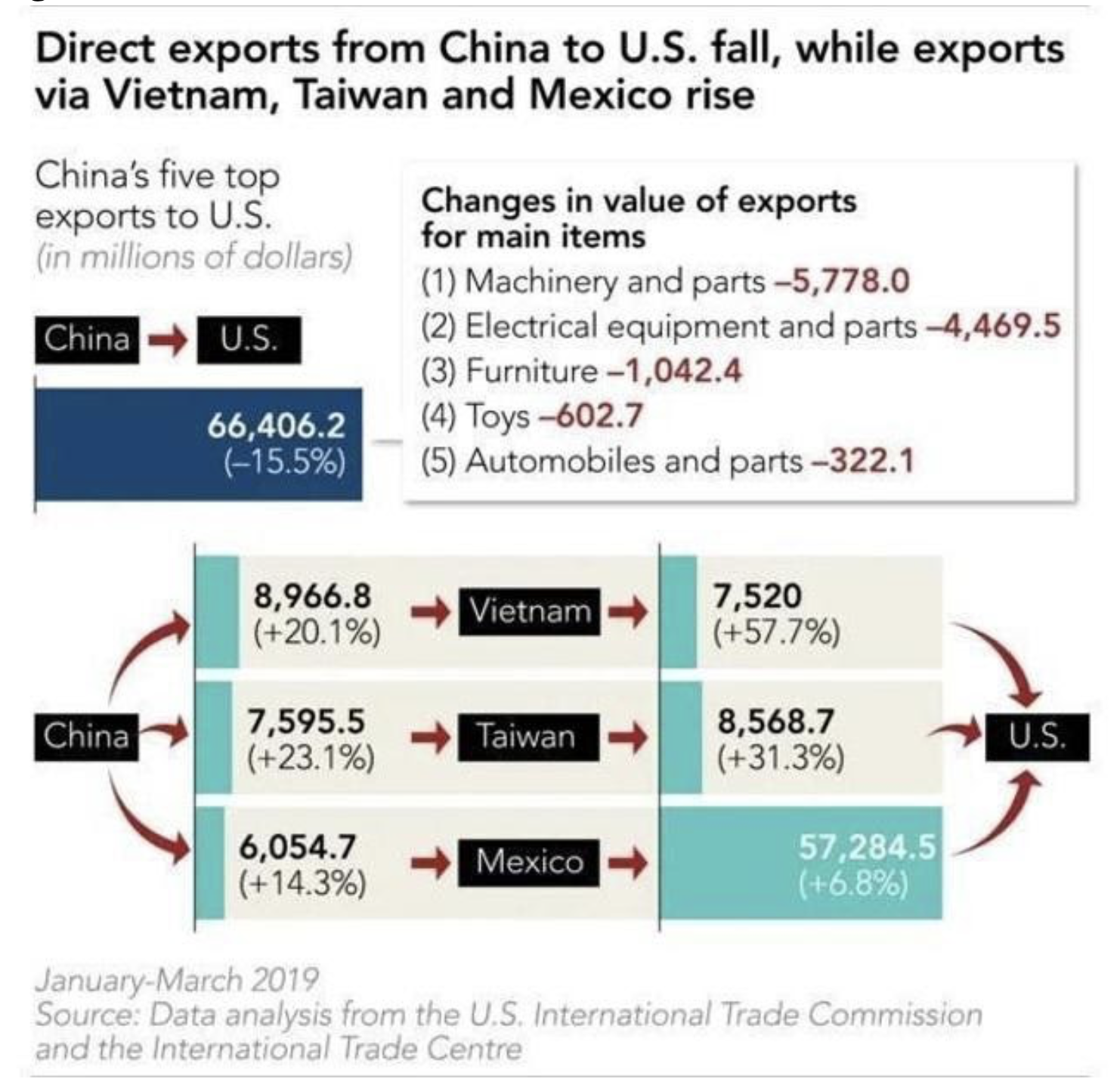

The pressure for diversified manufacturing started with the U.S.-China trade war. Nike and Williams-Sonoma are examples of companies that moved out of China and set up shop in countries like Germany and Vietnam to avoid the tariffs.

It did not take long for us to see results of the trade war. While U.S. goods imports from China declined by 5 percent year-on-year in H1 2019, imports from Vietnam were up 30.5 percent.

Other Southeast Asian countries have also had a robust trade growth with the United States: Cambodia saw an increase of 38.3 percent; Malaysia, 22 percent; Thailand, 19.6 percent; and Indonesia, 11.5 percent. Overall, U.S. imports originating from Southeast Asia in the first half of 2019 were up 23.1 percent compared to 2018. (see Fig. b)

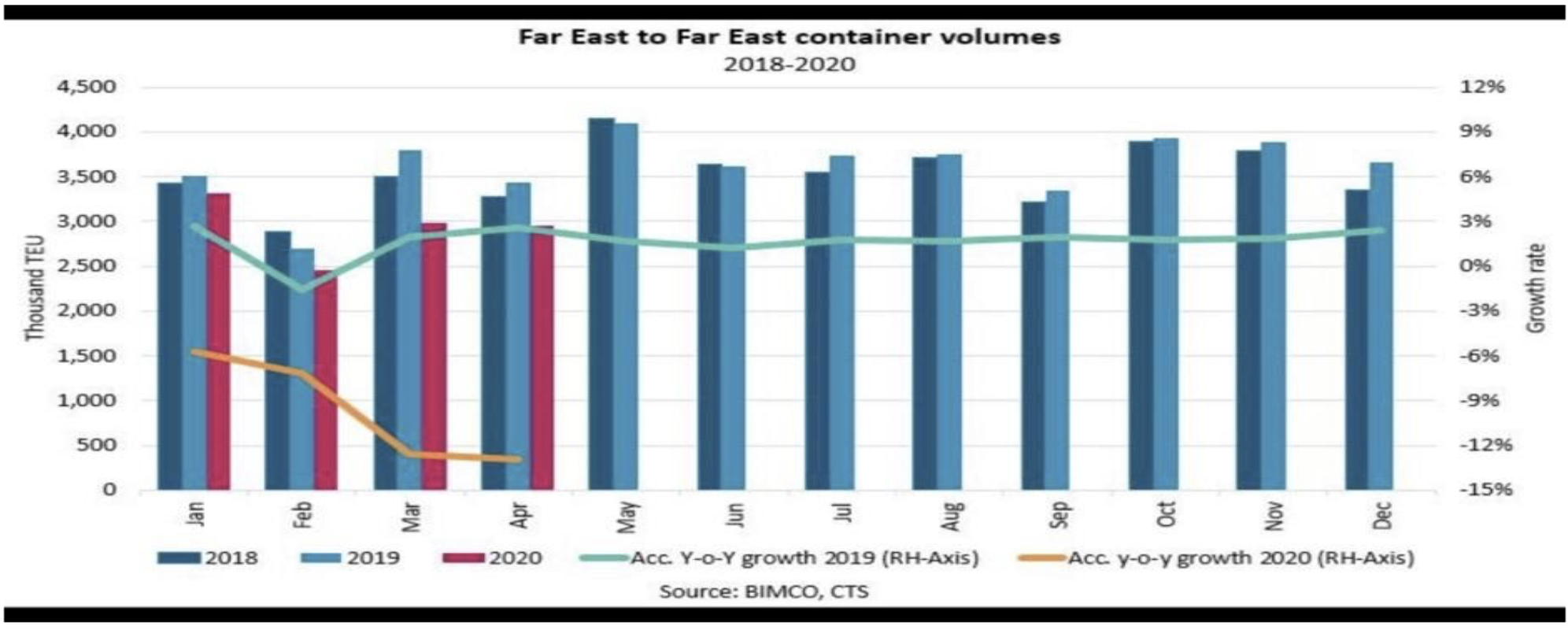

The intra-Asia trade lane stepped into the offshoring spotlight. (see Fig. c)

Vietnam Wins

One of the countries in this all-important intra-Asia pipeline is Vietnam. The country’s manufacturing expansion has also cultivated stronger trade relationships, which in turn have increased the country’s overall trade volumes.

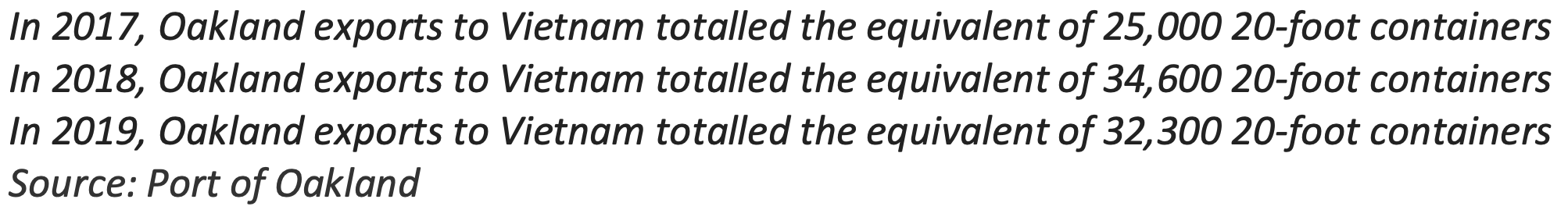

In 2018, the Port of Oakland added the direct service Pacific International Lines (PIL) to Vietnam. Since that direct service began, U.S. exports to Vietnam have increased:

“As middle-class economies expand in Vietnam and other Southeast Asian nations, the Port of Oakland finds new opportunities to export US goods,” explained Mike Zampa, communications director for the Port of Oakland. “These will be the growing markets for Oakland in the future.”

As with all sectors, the maritime industry directly benefits from a vibrant, growing, global economy. If trading partners are in an economic expansion, the demand for goods is greater. If a major trading partner starts to slow, or if there is an economic disruption, that kind of shock sparks fears of a global contagion, and demand diminishes. The dramatic dip in trade out of Vietnam and its recovery shows the immediate impact of COVID-19. (Fig. e)

The interconnectedness of the global economy exposes countries to both prosperity and slowdowns. Like a puzzle, each country is a vital piece to the overall picture. Without one, it is not complete. Export growth is the glue that binds the countries together. That growth thrives on the producers and consumers of the world. Economist Richard Baldwin once said, “Regional trade liberalization sweeps the globe like wildfire.”

Vietnam’s Evolving System of Trade

Vietnam’s growth in manufacturing and trade is a good example of how countries with less-developed infrastructure and ports are seizing the opportunity by attracting companies looking for a China alternative. Their growing pains offer key insights to companies on the vital pieces necessary to successfully create a robust supply chain.

The Vietnam coastline stretches 3,440 kilometers and is home to 320 ports including 44 large ports (including Hai Phong, Da Nang, Qui Nhon, and Ho Chi Minh City), and hundreds of smaller ports. Unfortunately, 80 percent of all container exports and imports travel through the smaller ports, according to a Vietnam Port Association (VPA) report. That means only the smaller ships can be loaded at the berth, which results in a time-consuming transshipment of containers onto larger vessels for their ocean voyage. It’s a hinderance that the country is actively looking to correct.

The VPA has quantified this extra link in the transportation chain at a cost of approximately $2.4 billion a year. The lack of deep ports isn’t the only obstacle in Vietnam. An underdeveloped intermodal system of roads and rails also adds to the transportation price tag. The VPA is aggressively seeking infrastructure investments in order to keep up with the increase of container volume.

Attracting investment dollars was one of the topics discussed in a recent Vietnam Maritime Administration (VMA) online conference. It was suggested that one way to encourage investment is to raise the price of the country’s low container loading-unloading service charges. The thinking was that, while a cheaper price is attractive for exporters and importers, it was unappealing for investors.

If prices were increased, the ROI trajectory would appeal to investors. The total capacity of Vietnam’s seaport system has skyrocketed from 73 million tons of cargo in the year 2000 to 650-700 million tons in 2020. The Vietnam government hopes to double that by 2030, with its $400-trillion master plan to deepen its ports in order to accommodate the world’s largest ships.

According to the Foreign Investment Agency (FIA), foreign direct investment in Vietnam increased to $38.2 billion in 2019, up 7.2 percent from 2018. One of the ways Vietnam has enticed foreign investors is through industrial zones with land rights, and the option to fully control their Vietnamese enterprise.

“Global retailers and distributors have started to invest mostly in Vietnam,” explained Peter Sand, Chief Shipping analyst at BIMCO. “FDI were second to none in 2018 for Vietnam. In 2019 they had to stop bringing more investments in, as they put focus on bringing existing [investments] online.”

The Vietnamese government has categorized the country into three major gateways for investment: North, Central, and South.

In the North, the Haiphong International Container Terminal opened a deep-water container port and terminal with a capability to handle 14,000-TEU vessels in 2018. This region services Hanoi and allows for direct shipping to the U.S. and the EU.

Central Vietnam’s Da Nang Ports streamline trade to Myanmar, Thailand and Laos. The Ho Chi Minh ports located in southern Vietnam account for 67 percent of goods moving in and out of Vietnam.

Jon Monroe, co-author of the Yangtze River World Report, says Vietnam’s master port and infrastructure plan takes a page from China’s 2002 master plan. “If this were a baseball game, we would be just finishing our third inning or 1/3rd of the way through,” he said. “Long- term, Vietnam will be a close number two to China as an export powerhouse.”

Just like the United States, where industries are in specific areas around the country, Vietnam has also developed similar business regions to match talent with logistics and business. Approximately 3,883 new projects in 19 sectors were licensed in 2019. The investment capital topped $362.5 billion. Manufacturing and processing constituted 65 percent of the coffers, worth $24.56 billion. Real estate came in second at $3.88 billion, followed by retail and wholesale.

Vietnam’s Growth Model

China has been successful in attracting businesses because of its intricate intramodal system, ports, and low-cost, high-quality workers. You cannot be a successful hub of manufacturing and production without these components. This is a blueprint Vietnam is in the process of emulating.

The garment and textile industries are located in the North. According to Dezan Shira and Associates, North Vietnam is considered an optimal location for a textile or garment plant because of its proximity to China for the intra-Asia movement of semi-finished goods.

Central Vietnam is the country’s hub for technology, where the Da Nang city has invested $60 million in a new airport and over $90 million in a new road infrastructure.

“Asia has the best talent pool needed for [the manufacturing] sector,” explained Daniel Ives, managing director at Wedbush Securities. “If you need to diversify your manufacturing portfolio, Northern and Southern Vietnam are good choices, and eventually over time, India.

Unfortunately, there are no ‘near-shoring’ opportunities in Latin America and Mexico. That region does not offer the engineers and tech talent needed.”

Southern Vietnam has the key Saigon Port system, which is the 26th largest port in the world and the 5th largest among Asean Ports. Footwear and furniture manufacturing are located around the Ho Chi Minh Ports.

“This region is ideal for retail because of its talent base,” explained Rick Helfenbein, former chairman and CEO, American Apparel and Footwear Association. “At my prior company, we had manufacturing facilities in Mexico for five years but, after a disappointing production run, we eventually moved the production to China. Retail [sourcing] and manufacturing companies have now expanded out of China into the intra-Asia corridor. Keep in mind that while it does expand the supply chain, you are never fully out of China because of raw material supply. China is still a critical component in this region’s manufacturing equation. Your managers could be from China or [manage] the pieces that help complete the overall product are produced there. This link created a disruption early in the COVID-19 supply chain, because even if the plant outside of China was running, China was still closed at the time.”

Flow of Trade Shows Growing Pains

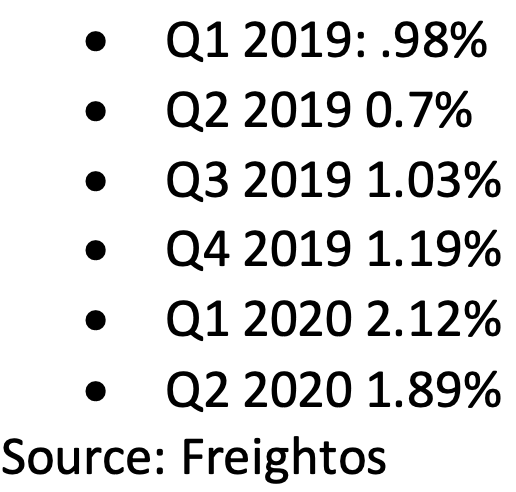

To follow the increase in freight traveling out of Vietnam, one of the barometers is the freight inquires on the Freightos marketplace. (see Fig. f)

“We are seeing an interesting trend in the search history,” explained Eytan Buchman, CMOof Freightos. “We have seen tariffs pushing more sourcing to Vietnam, with a final spike in Q1. But COVID-19 seems to have pushed more people back to China, possibly because manufacturing there had recovered faster.”

This trend is supported by Vietnam’s port and intermodal data. (see Fig. g)

These growing pains will persist as Vietnam’s supplier market is still developing. Companies looking to set up manufacturing plants must assess the local market and see if the possible location has both the ability and capacity to support their production needs. Major cities offer airports, as well as a highway and road system. Moving outside of the urban areas, however, all three regions need further development.

“The river system still needs to be developed along with the smaller ports to develop a transhipment system,” explained Monroe. “Central Vietnam is still underdeveloped, and the port system requires major investment for the country to achieve its goals.”

Other Alternatives

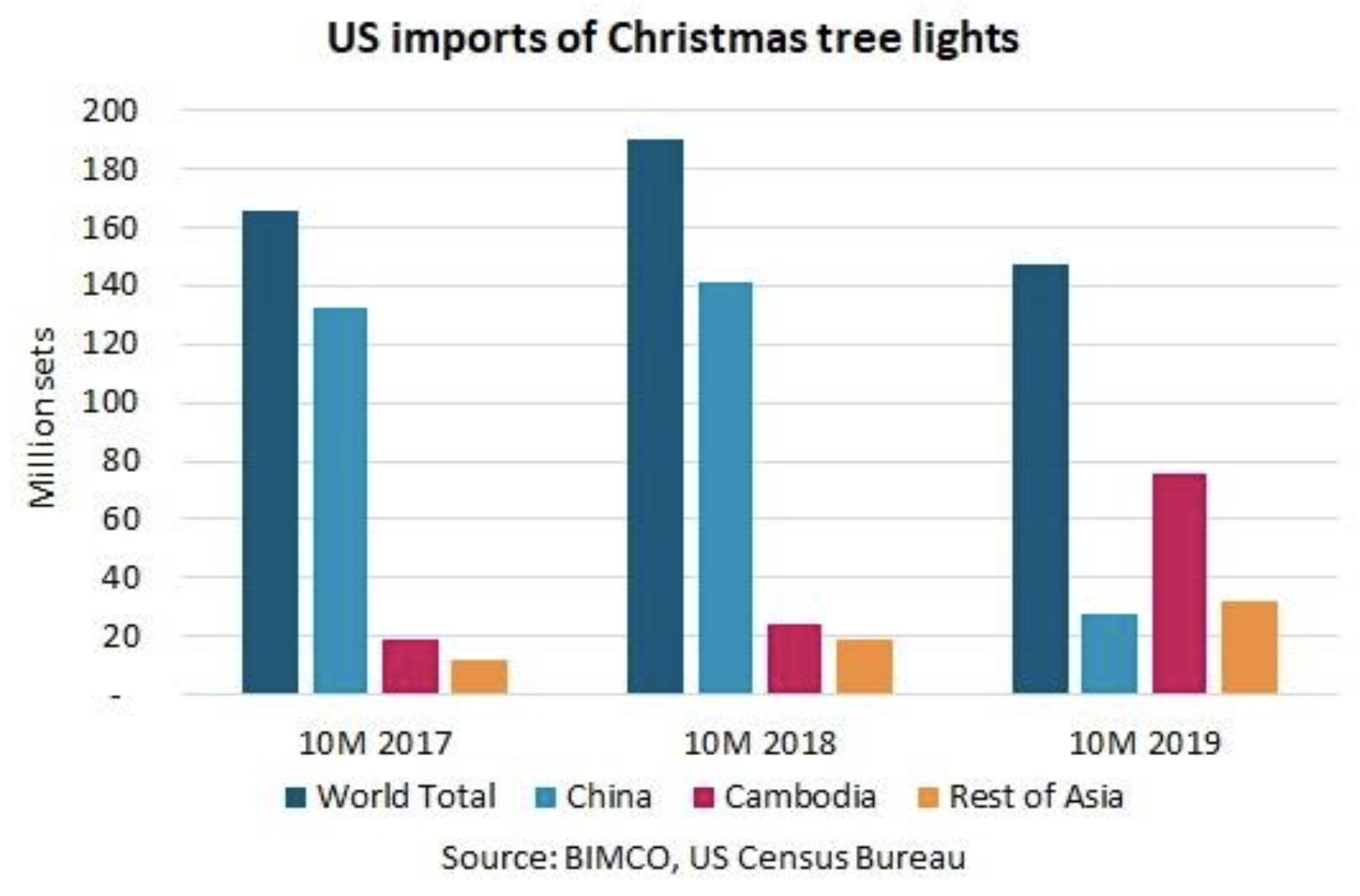

Vietnam is not the only Asian country seeing a positive inflow of manufacturing business as companies pull production out of China.

The U.S. imports reshuffle of Christmas lights from China to Cambodia is an example of this shift. (see Fig. j)

Technology may also find another home in India, but there are challenges tech investors are keeping a close eye on. “India has the talent, but elements of road and port infrastructure are lagging,” said Ives. “The fact China became a production hub of the world is not accidental. They have taken a concerted effort to create an attractive destination.”

China’s efforts took decades to build and fortify. So, while there is an intense cry for a decoupling from China, the flow of trade and supply chain provides a reality check and a timeline for any such move.

Authors:

Lori Ann LaRocco

Lori Ann LaRocco is senior editor of guests for CNBC business news. She coordinates high profile political, titans of industry interviews and special multi-million dollar on-location productions for all shows on the network. LaRocco is a maritime trade columnist for American Shipper, the author of: “Trade War: Containers Don’t Lie, Navigating the Bluster” (Marine Money Inc., 2019) “Dynasties of the Sea: The Untold Stories of the Postwar Shipping Pioneers” (Marine Money Inc., 2018), “Opportunity Knocking” (Agate Publishing, 2014), “Dynasties of the Sea: The Ships and Entrepreneurs Who Ushered in the Era of Free Trade” (Marine Money, 2012), and “Thriving in the New Economy: Lessons from Today’s Top Business Minds” (Wiley, 2010).Prior to joining CNBC in 2000, LaRocco was an anchor, reporter and assignment editor in various local news markets around the United States.

Nick Vyas, Ed.D.

BS, MBA California Polytechnic University, Pomona Ed.D. University of Southern California

EDUCATOR. KEYNOTE SPEAKER. AUTHOR. GSCM SPECIALIST. INDUSTRY ADVISOR. THOUGHT LEADER

Dr. Nick Vyas is an educator, thought leader, author, keynote speaker, ASQ Fellow, Chair of the ASQ Lean Division, and advisor to leaders in the worlds of supply-chain practice and policy. As the Executive Director and founder of Center for Global Supply Chain Management (CGSCM), and Academic Director, USC Marshall MS GSCM program, Vyas educates the next generation of business leaders.

An early proponent of the need to recognize the pivotal role of global supply chain management in international trade policy trends and economic growth, Dr. Vyas has frequently contributed articles and opinion to reputed media platforms such as Supply Chain Management Review (SCMR), NPR, KCRW, CBS News, The Economist, Los Angeles Times, Rachel Maddow Show, and the LA Business Journal. He is the co-author of Blockchain and the Supply Chain: Concepts, Strategies and Practical Applications, a book that highlights industry use cases to illustrate the significance of blockchain as an enabler and a key driver for solutions in global supply chain networks.

As a recognized thought leader, Vyas delivers keynote addresses at conferences held across the globe, particularly in countries home to economies in transition such as Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Singapore, and the Dominican Republic, on matters concerning global trade, disruptive technologies and their impact on global supply chain management and operations.

An authority on global SCM and Logistics, Vyas has led business and cultural transformation for Fortune 100 M&A Companies over the last 30 years. He also serves as a member of the U.S. Department of Commerce Advisory Committee on Supply Chain Competitiveness.

He has received his Doctor of Education from the USC, with a published dissertation on Conceptualization of Higher Education Excellence System (HEES): Use of Advance Data Analytics and Blended Quality Management.

Currently, Dr. Vyas is working with other experts and universities on a supply chain healthcare consortium initiative to: create and provide aggregate demand forecast for running 12 weeks for the hospital inventory model; secure/aggregate demand allocation by city/state to create cooperative procurement opportunities; help guide our local hospital network through supply chain issues, including logistics, distribution and last-mile deliveries; create a network of alliances at the Local/State level to facilitate synchronized execution.