The world will never be the same again. Black swan events such as the Covid-19 crisis leave the world scathed and wrung inside out, compelling people to identify and fix the frailties of social, political, and economic systems. The fixing can be either benign or drastic, depending on the shared values of a society. The Black Death (1347 – 1351) saw a near-total disappearance of serfdom in Western Europe, doubling of wages for English farmworkers, and the emergence of the middle class. The 1918 Influenza pandemic strengthened the claim of women in America to economic remuneration and provided the first unifying impetus to India’s freedom movement.

The ongoing Covid-19 crisis is making deep and sweeping changes to global and regional economies. Some of these changes are going to be ephemeral and some others, permanent. American retail is seeing a dramatic shift in consumer behavior. Some of these trends may be everlasting, such as an increased preference for online grocery shopping. Worldwide, education has gone online, and the nascent idea of a universal basic income (UBI) just became a reality with the new stimulus law.

There is another trend which has been underway in recent years. The present crisis may accelerate the trend one way or another. That trend is the reshaping of global supply chains.

China’s re-imagination of the world’s supply chains and the trade war

In a recently written two-part blog, I explored how the US-China trade war was really about the dominance of global supply chains. The roots of the trade war go back further than the year (2015-2016). It became a campaign issue in America. The seeds of the conflict were sown in the early 2010s when academics in the US and Europe began to notice dramatic shifts in patterns of world trade. Calling this phenomenon the China Shock, scholars began to document how China’s growing economic influence was not only making the US and Europe dependent on China’s factories; it was also beginning to exacerbate America’s wage gap.

For context, let’s take a quick look at how China came to be a significant player in the world’s supply chains. China’s economic ascent began with its 1990s reforms and was subsequently boosted by its entry into the WTO in 2001. That helped China grow its share of the world’s manufacturing exports from 6 percent in 2000 to 18 percent in 2012 (Fig. A). During the same period between 2000 and 2012, the USA’s share decreased from 18 percent to 9 percent.

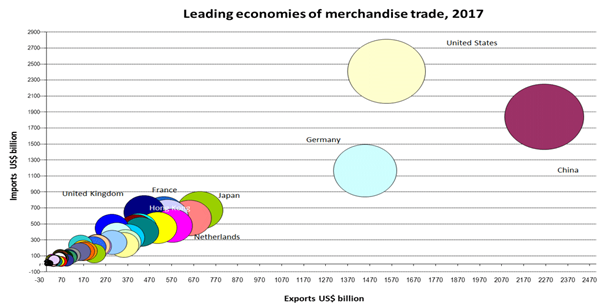

In 2018, China was the world’s biggest goods exporter with $2.49 trillion of exports, with the US in second place with $1.7 trillion of goods exports, followed by Germany and Japan. Not just exports, China has been buying goods at a greater rate. In 2013, China surpassed the US as the most significant trading nation. Its share of global trade increased substantially from a mere 1.9 percent in 2000 to 11.5 percent in 2017, placing it ahead of the US. (Fig. B)

Fig A : Source: MAPI

Fig B : Source : WTO

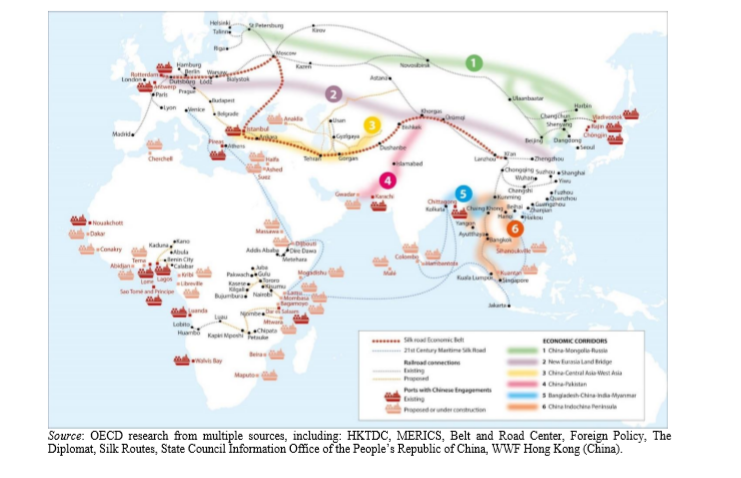

China’s hunger for trade growth has been complemented by its desire to consolidate its influence on the ground. The country’s ambitious multibillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) unveiled in 2013 has spawned railroad and infrastructure projects stretching from China to Europe, and created a sea-based network of shipping lanes and ports stretching from Kyaukpyu port in Myanmar to Hambantota in Sri Lanka right up to the port of Obock on the Horn of Africa (Figure C).

Fig C : The BRI Expanse. Source: OECD, 2018

But physical supply chains have geographical limitations. It is the digital layer that provides more significant scope and reaches to supply chains. Fueled by Silicon Valley’s venture capital and a top-down growth model, China has taken significant strides in all major technology sectors. The biggest lead is in 5G technology, which is set to transform the world of connected devices. Out of the world’s top five 5G infrastructure equipment, leaders – Ericsson, Huawei, Nokia, Samsung, and ZTE – two are Chinese companies, one of which is banned in the US, and not one is American.

Likewise, China has fast emerged as a leader in other significant technological domains, namely fintech, big data, artificial intelligence, e-commerce, cloud computing, and ICT exports. China has poured in substantial investments and resources into these areas during the past two decades, where it today rubs shoulders with global leaders.

But the US-China trade war of recent years has made serious dents into this fantastic growth story.

Apart from witnessing an economic growth of 6.1 percent, its slowest in three decades, US-linked manufacturing began to shift away from China. The biggest beneficiaries have been other Asian countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, that offer better labor and production costs. Vietnam’s US-bound exports surged to such an extent (36 percent) last July that it drew scrutiny and punitive tariffs from the US. According to at least one report, foreign companies were being seen queuing up at Vietnam’s industrial parks.

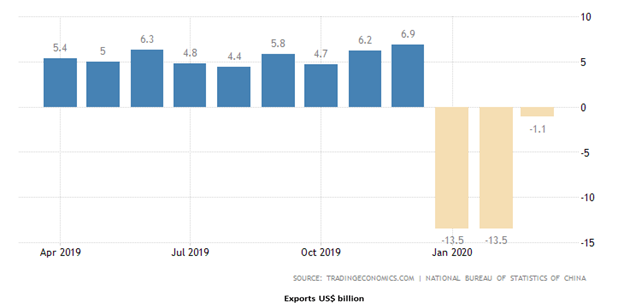

Closer to home, Mexico and Canada pushed China down the ranks to become the USA’s number one and two trading partners. Still, amid all the back and forth of tariff impositions, China’s industrial production managed to climb back to a respectable 6.9 percent in December 2019. In short, trade tensions began to reshape global supply chains away from China, slowly but surely.

Then Covid-19 struck (Fig D).

Fig D : China’s Industrial Production: April 2019 – March 2020. Source: Trading Economics

As the specter of a pandemic loomed in mid-January, supply chains worldwide, particularly those linked to China, came to a standstill and have stayed so thus far, except those ferrying essential supplies.

As economies worldwide remain in a state of limbo, economists and entrepreneurs are beginning to wonder: what will post-COVID-19 supply chains look like?

Decoupling, not deglobalization:

Times of the deep crisis that generate demand shockwaves are followed by waves of deglobalization i.e., periods of history when economic dependence and integration between nations see a continued decline. Two periods of the economic crisis in the last century have followed deglobalization – during the 1930s following the Great Depression, and the early-2010s following the 2008 financial crisis.

The overall impact of the Covid-19 crisis is not clear since it is far from over. But one thing is clear –the economic implications are going to be bigger than ever, because a hyper-connected world has been in a position, for the first time in history, to launch a concerted response to a pandemic. In other words, the combined impact of the disease and the cure is going to have far-reaching implications for the global economy, some negative, but mostly, hopefully positive.

Global supply chains, already undergoing a process of churn and transformation due to the trade war, looked very different in December last year from what they did a few years ago, and that caused rising concern among scholars of a post-trade war period of deglobalization.

Now the Covid-19 crisis has unfortunately but understandably deepened concerns about China-linked trade and has led experts to predict the third wave of deglobalization.

However, I am a firm believer that instead of deglobalization, we will see a decoupling of global supply chains. Let me explain to you what I mean by the term: instead of having a worldwide network of interconnected supply chain nodes, we will have regionally concentrated supply chain networks, each connected with other regional supply chain network through a decoupling point. A decoupling point is a concept in inventory management where a specific inventory-holding point is established close to the operational zone. The decoupling point acts as both a strategic distribution hub and a safety buffer that protects that regional supply chain network from demand shocks. I understand that we are going to see such decoupled supply chain networks concentrated around South East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, North America, and other economic hubs, where each hub is connected to the others, yet protected from demand shockwaves the likes of which are being felt today.

There are several reasons why I think global trade will see a decoupling and not a deglobalization of supply chains. First and the most obvious reason is that a deglobalization is not feasible – there is too much at stake. The world is far more interdependent than it was in the 1920s or even the early-2010s (Figure E).

Fig E : A historical view of global exports. Source: Our World In Data

Second, decoupling will be a unique way to solve two paradoxical issues at once: one, significantly reduce the heavy reliance on China and therefore make regional supply chains more resilient to any shocks emanating from behind the Great Wall; and two, do this without marginalizing China. Any solution, such as deglobalization, which seeks to exclude or marginalize China is not only undoable; it’s also foolhardy. China’s investments in BRI and its underpinning technologies over the last decade have been made in preparation for its divestment from a purely manufacturing-based economy. China has made substantial investments in ASEAN countries, Southeast Asia, and Africa intending to be able to run diversified supply chains remotely. We need a global supply chain that works with, and not against China’s strengths.

Third, there is a legacy already in place that provides a blueprint for decoupled supply chain networks. Ever since November 1982, when Honda’s Marysville, Ohio-based factory rolled out its first Accord, Japanese manufacturers have known the advantages of selling a Made-in-America car to the Americans. This has been done before, and it can be done again.

Decoupling of the supply chain is the only way to build in resilience and agility into supply chain networks. Would that be easy or cheap? No. But it needs to be done because we cannot afford a $2 trillion bailout every time a virus makes an interspecies leap in some other part of the world.

In a perfect future, supply chain networks will be customer-centric, built atop digitalized platforms and robotics, interconnected with other networks through decoupling points that will relay a zero-latency response time to demand fluctuations. In the past few months, our supply chains failed time and again to respond to this crisis because supply chain networks still lack the level of digitalization that other industries do. With proper digitalization, we could sense demand of, say, testing kits and PPEs and essential supplies just in time and communicate that to alternative networks.

In my view, our civilization can’t afford to experience end-to-end disruption of global supply chains the way experience during the COVID-19. Also, we can’t solve the issue of global supply chain resiliency and agility without the decoupling of the supply chains. In addition, the Capex justification and ROI can only be realized by integrating emerging technologies, including AI, ML, Blockchains, and many others, to capitalize on the potential of the digital frontier, which is efficient, effective, resilient, and eco-friendly.

Follow USC Randall R. Kendrick GSCI: https://www.linkedin.com/

Follow Dr. Vyas on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/